Lately I’ve been getting into Wikimedia Commons, uploading artwork and organizing the autism stuff. While organizing, I ran across the “Charlie” problem.

I believe the Charlie problem illustrates one of the differences in non-autistic versus autistic thinking… as well as the dangers of using non-autistic assumptions to dismiss autistic abilities.

The Charlie problem

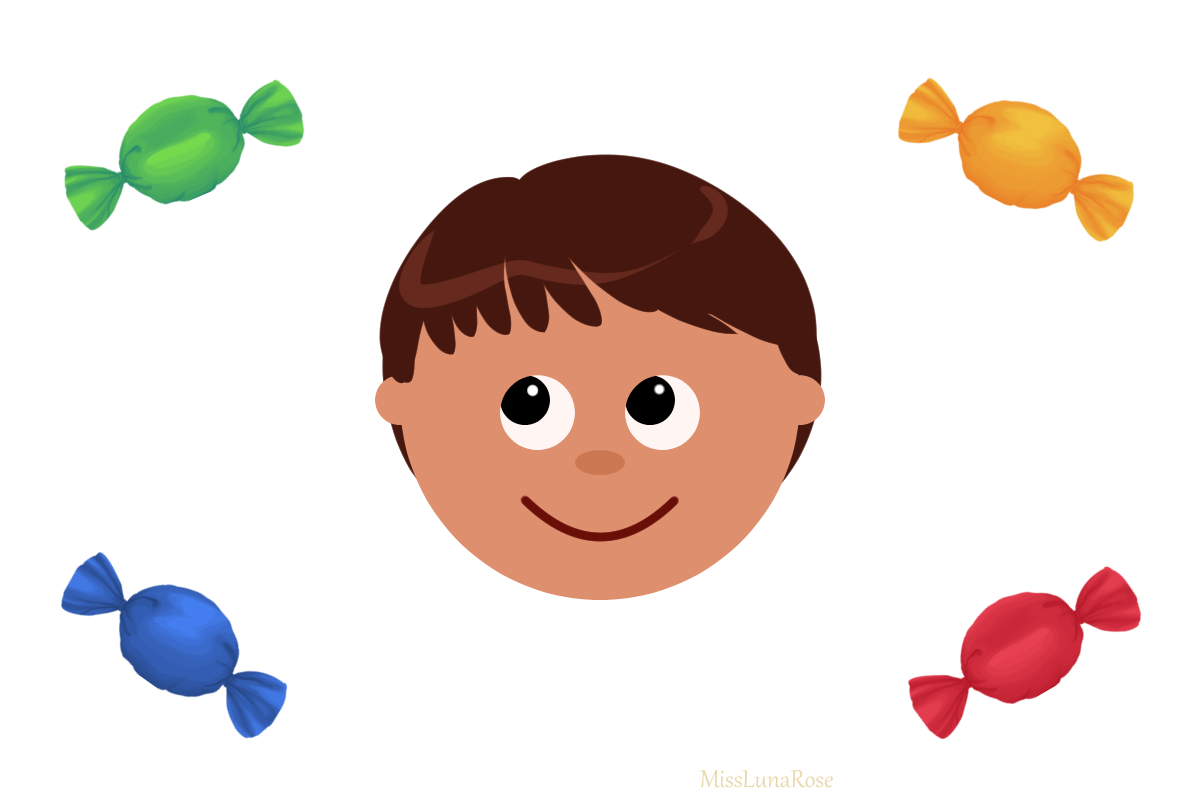

Around 1995, Simon Baron-Cohen et al showed a picture to autistic and non-autistic children. While I can’t find the original study, I believe that the kids were asked 2 questions:

- Which candy is Charlie looking at?

- Which candy does Charlie want?

Unless you’re color-blind or literally blind, you probably thought that Charlie was looking at the green candy.

In the study, the children also could tell which candy Charlie was looking at. (Big surprise.)

But here’s where things get interesting: the non-autistic kids said that Charlie wanted that candy, while the autistic kids weren’t sure.

(Please feel free to share whether your answer was “green” or “I don’t know” in the comments.)

According to researchers, this is because autistic kids lack the basic understanding that people look at the things they want.

But can we be sure that’s what’s going on here?

My autistic reasoning

When I saw that the picture was supposed to suggest what Charlie wanted, I was startled. “Why on earth would you assume that?” I asked myself. “Non-autistics are so weird, what the heck!”

According to my 23-year-old autistic brain, this picture doesn’t mean that Charlie wants the green candy. All it means is that he’s looking at it.

As I looked at the picture, I thought…

- Maybe he’s still weighing his options.

- Perhaps he’s trying to remember if he’s eaten the green type of candy before, and whether he liked it.

- Maybe he’s staring off into space daydreaming.

- Perhaps he plans to grab all 4 candies and run off before the experimenter could stop him.

He could be looking at the green candy because he wants it, but there are multiple other explanations for his eye gaze.

Autistic people tend not to make eye contact, and we don’t always look at the things we’re thinking about. (I stare off into space when I’m thinking really hard about what someone is saying to me.) To the autistic mind, the direction of the eyes does not always signify the focus of the mind.

If Charlie kept staring at the green candy, that could mean the green candy is important to him. But I can’t be sure just by looking at his eyes.

So I don’t know what Charlie wants. To me, the only logical way to find out would be to either (1) wait for Charlie to make a decision, or (2) just ask him what he wants.

Thus, I find Baron-Cohen et al’s assertion flawed. We can know what the autistic kids said, but we can’t be certain if it’s related to a theory of mind deficit, or if it’s just because the autistic kids are more reluctant to ascribe motivation based on limited evidence.

Implications

While individual brains vary, I think that this little story tells us a few interesting lessons:

- Non-autistics tend to assume that everyone thinks in the same way. Thus, especially if you’re a non-autistic person with an autistic loved one, it’s important to remind yourself that you shouldn’t jump to conclusions about why they’re behaving a certain way. You could easily be incorrect.

- Autistics can keep in mind that with non-autistics, gaze usually equals intent. (For example, a non-autistic person might look at a door because they want to leave.)

If the majority of brains work similarly to yours, then you can imagine yourself in their shoes and make assumptions that are likely correct. But if the majority of brains are different from yours, then you quickly learn that it’s hard to assume what others are thinking.

Thus, autistics quickly learn that others are mysterious, whereas non-autistics learn that others are predictable.

In fact, I think that recognizing that others likely think differently from oneself would be adaptive in autistic people.

(Of course, I’m not going to deny biological differences between autistic and non-autistic brains. Those could be at play too. I just don’t understand them well enough to comment.)

Anyway, I think non-autistics may take for granted the fact that the average brain is quite similar to theirs. So if you’re a non-autistic person interacting with an autistic person, it’s important to step out of that perspective and acknowledge that the reasons behind their behavior might be different from what you assume.

Or, in short: When in doubt, just ask the other person what they’re thinking.

And now I run an experiment because I can.

I wanted to run a small unprofessional replica of the study using my family as test subjects. (Don’t worry, I have a license.)

Setup

The experiment took place in my room. Due to the small sample size, the fact that I only tested my relatives, and the Mamma Mia music playing in the background, I will not be submitting my study for peer review.

My hypotheses:

- All family members will recognize that he’s looking at the green candy, because duh.

- Mom, Dad, and Stella will say he wants the green one.

- Neil, who shows signs of being autistic or Broad Autism Phenotype, is the wild card.

I also chose to ask each family member to explain their answer to the second question.

My results

Unsurprisingly, every member of the all-adult study population was able to tell that Charlie was looking at the green candy.

Here’s a table of my results for question 2 (what Charlie wants).

| Person | Neurodivergent? | Paused before answering | Said green |

| Stella | Down syndrome | Yes | Yes |

| Dad | Neurotypical | No | Yes |

| Mom | Likely alexithymia* | Yes | Yes |

| Cousin Neil | Autistic traits, no dx | Yes | Yes |

*Alexithymia is a subclinical personality trait that makes it hard to identify emotions. Many autistics are alexithymic. I’m pretty sure that my autism came from Mom’s side of the family.

Here were the explanations they gave for their answer.

- Stella said: “Because he was looking at the green.”

- Dad said: “Because he’s smiling as he’s looking at it.”

- Mom said: “”‘Cause he’s looking at it. That suggests maybe he’s drawn to it.”

- Neil said “Because if he wasn’t interested in something, why would he be looking at it?”

It seems that, for non-autistics, looking at something suggests that you are interested in it. Non-autistics rely on this idea when interpreting the gaze of others.

My mom later said that, during her pause, she was considering the (debunked) theory that people look in certain directions based on what they’re thinking about.

I asked my cousin why he paused. He said that he paused because the test seemed so straightforward that he was wondering if it was a trick question. This confusion (“why is it so easy?”) is probably a downside to testing adults instead of children.

Discussion

Obviously we can’t draw any sweeping conclusions from this informal 4-person study of adults from the same family.

But I did find the pauses interesting.

Stella’s pause could be explained by slow thinking. While she has theory of mind, she doesn’t always grasp it intuitively. (During playtime, her dolls tend to have a hive mind, and they lack distinct personalities.)

Interpreting my mom’s and cousin’s pauses poses a challenge. Were they just wondering why I asked them such a simple question? Or were their brains slower to associate eye gaze with desire? Neil shows signs of autism and my mom shows signs of alexithymia (a trait most autistic people have). Could their hesitation be linked to neurodivergence, or is this just what happens when you ask a ridiculously simple question to an intelligent adult?

I don’t know. As the only professionally-diagnosed autistic of the family, I’m loathe to assume other’s thoughts based on limited behavioral data.

Anyway, I believe that Baron-Cohen’s experiment was limited for several reasons:

- It jumped to conclusions about why autistic kids didn’t say the “correct” answer. (We don’t know whether it was lack of understanding or reluctance to assume.)

- The kids may have felt pressured to pick an answer as opposed to saying “there’s insufficient evidence.” They may not have been eloquent enough to explain their hesitance if it existed.

- The unnatural study environment could be confusing or uninteresting. Without incentive or a real-life person in the example, kids could get “wrong” answers despite having the knowledge in real life.

I don’t deny that some autistic kids have delays in developing theory of mind, or that some autistic kids might not grasp certain concepts. But I do believe that Mr. Baron-Cohen has a habit of making broad claims without sufficient evidence, and I think that he could have jumped to conclusions here.

Autistic thinking is different. That doesn’t mean it’s always deficient.

What about you?

What did you think when you first saw the picture?

If you’re interested, comment and say:

- How you interpreted Charlie’s intent

- Whether you’re autistic

- Whether you’re alexithymic or neurodivergent

- Your own ideas about neurodiversity and theory of mind

This obviously doesn’t carry the same scientific weight as a peer-reviewed study, but it’s fun to share ideas and theories. (And don’t be afraid to speak up even if you didn’t follow the autistic/non-autistic pattern.)

Exploring differences in autistic vs. non-autistic thinking is always fascinating to me, and I love hearing different perspectives and learning about how different people think in different ways.

So, what’s on your mind? I’ll never know unless you tell me.

“But here’s where things get interesting: the non-autistic kids said that Charlie wanted that candy, while the autistic kids weren’t sure.”

That’s because the allistic kids were imputing motives of their own to Charlie, whereas the autistic kids, who have much better theory of mind, recognised that Charlie’s motives might be different to their own and honestly expressed that line of thinking. Just sayin’. As for why Charlie’s looking at the green-wrapped sweet, he might just like the colour. I’m autistic (formally identified) and alexithymic.

LikeLike

I think sometimes non-autistics forget that other people’s brains are fundamentally unknowable to us, and while we can guess, we can’t be certain.

LikeLike

In addition to my last comment. I asked my son who is diagnosed and he very quickly said green. When I asked why, he said because he is looking at it.

Interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, it’s certainly not going to be universal that all autistics think the same way or that all non-autistics think the same way!

LikeLike

Undiagnosed female adult of three children all diagnosed. I paused and noticed he was looking at green sweet, thought well he is looking at the green sweet, I wonder if that means it might be that one he wants, then concluded that must be the answer because I couldn’t think of any other possible ways of knowing. Process of elimination made my decision.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds like a highly logical way to think.

LikeLike

I am Autistic and, nope, I don’t know what Charlie wants! So as an adult 29 years old Autistic woman I would blatantly fail this „test“ 🤣

There are probably so many reasons why people look at an object or a particular point in space… How should or could I know (without them Saying it or providing other more concrete Information) why they look at something? So no, no idea which candy charlie wants or if he wants one at all. He could want the blue one, the red one, the yellow one, the green one, any combination of those, all of them, none of them,…. And all of these possibilities have the same probability, in my opinion. Simply looking at something does not give an accurate information about what one wants. Not even close in my opinion. And honestly: who am I to claim to know from just this rare information what the person the drawing is supposed to symbolize wants? really, no idea. And i think it’s really strange that there are people claiming to know what this cartoon character „wants“ and that there is an only „correct“ answer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree! It is odd to think that some people say that looking equals wanting. It’s limited data.

LikeLike

Hi!

I realise that this might be a bit of an old post – it’s a bit of a read the entirety of autism blogs type week for me at the moment. I’m really glad I’ve found this one, because your stuff at WikiHow was basically the main stuff I was looking at when I was getting my diagnosis a few years back, and I really like your style (and substance).

I had read an article mentioning this before I actually saw the picture, so maybe that might have had the potential to change my result, so idk

But looking at that picture it didn’t even seem to me like he was looking at the green sweet. He’s looking upwards to the right (his right, obviously, not my right), and when I do that myself, it is usually when I’m thinking (in fact, my bitmoji on snapchat has this expression in perpetuity as my symbol – interpret that as you will). I think a large problem in working out what he’s looking at is the fact that he is 2D (why would they do that? surely it makes it much harder to work out accurately what he’s looking at), so it looks to me as if he is just staring into space. Secondly, the fact is that he is obviously not a real human being – who knows if he has wants at all? Even this fact would make me put a not sure answer, though I might have put otherwise if it was a real person looking at an eerily floating green sweet (though in that case, it would probably be that they are just very confused that gravity seems to have changed it’s mechanism). This very simple illustration style is, to my point of view, a factor that should have had a control for – I could well imagine that some people who would answer unsure or something to what does Charlie want would be able to do a lot better if they saw a photo, or even more likely than that a video.

As you might have guessed from my intro, I was diagnosed as autistic some years ago, when I was about 14. I put it that way because there were some things I was seriously confused about for a while, firstly because in essence they did the same things with me (a kid just starting on GCSEs and top of the class) as they did with five year olds. Secondly because at the end they basically said they could diagnose me but only if I was sure I wanted to be, because they didn’t have to and they weren’t sure I was affected in my everyday life (like, seriously… I was there in what was quite a scary environment (yellow walls and everything) and they thought I might not want a diagnosis?! and I had told them clearly I thought..). This made me question the whole thing because though I was doing this through the official channels (NHS), it seemed like wether they diagnosed me was really just a matter of ‘hey do you want me to put autism?’ – I thought it was meant to be a way of finding out and being validated for who I was, and this made me unsure of the whole system. Thirdly, and probably the biggest issue was that I go to a boarding school (long story) and so they were supposed to send the letter with the diagnosis to my GP, and to my parents (who live in a different area of the country, so are in a different NHS trust/area or something). Nothing ever came to my parent’s house. So I didn’t get to see what they’d actually put down. I don’t know what happened to the one meant to be sent to the GP. I think it must have arrived, because finally this year they’ve mentioned it, but when we tried to ask (a few months after we should have had the letter) we got no reply. So for years I was slightly unsure wether in reality I had been diagnosed at all. I’m pretty sure I have been, and I have applied this week to see my medical record (which is a legal thing that they have to reveal) so I’m hoping to get some clarity, but obviously they are rather inundated with stuff at the moment due to the cornoavirus, so it could still be a while…

I don’t think I’m ale….whatever it is. I only heard of it specifically yesterday, though I’d heard the thing about autistic people often not being able to label emotions. Sometimes when a meltdown is coming on I don’t realise until I think about why I’m rocking or repeating rhythms, but I think that’s a different thing because it’s specific to that circumstance.

With theory of mind and stuff, I get rather confused at the idea. I can do the doll test thingy easily, but if I try to think about everyday life, I know that I cannot know in a lot of circumstances what people will have experienced etc. and therefore what they know or how they will react. That is not an impairment, it is a logical fact. I will sometimes get it wrong due to probability, so I usually prefer to ask if there’s something I’m not sure about. But in general I’m pretty sure I’m just as good at this theory of mind thing as other people (and the majority of people to be honest don’t seem great at it unless they’ve known someone the whole of their life if I understand it correctly).

Something I considered while writing this is maybe partially what wonders about autistic people and theory of mind come down to is that autistic people are less likely to state as fact things they are not fully sure of, where there could be ambiguities or other interpretations. Just an idea.

Anyway, I’m really sorry that this has been such a long comment, it made me think quite a bit and I’ve had some stuff that I kind of needed to just vent as well I guess.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad that my post gave you things to think about. And those are good points: Charlie could easily be thinking to himself and not looking at the green candy at all. I agree that sometimes non-autistics are quicker to draw conclusions than autistics are, for better or for worse.

It sounds no fun, lacking answers right now and being unable to get them. I too was hoping for help with a diagnosis (potential Ehlers-Danlos syndrome) but am holding off until the coronavirus crisis passes. I wish I had a definitive name for what is going on with me.

Alexithymia is an interesting condition that isn’t officially diagnosed but can be useful to self-identify if it’s present. I recommend reading up a little if you’re curious. (I have and I found it interesting.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

“If you’re interested, comment and say:

How you interpreted Charlie’s intent

Whether you’re autistic

Whether you’re alexithymic or neurodivergent

Your own ideas about neurodiversity and theory of mind”

1. Charlie’s intent – he was looking at all the candies at some time or another.

I do not know if he really wanted the green candy any more than the others. If his eyes were looking up he would have seen the yellow candy – if they were looking down the red one. I do not think he would have wanted the blue one very much.

Hopefully Charlie is not hemiplegic/left-sided blind [this is a neurological thing Oliver Sacks would write about] – I wanted to talk about left/right side neglect.

There is probably a 1/4 chance he would have got the candy he wanted – unless the one he wanted was purple or orange or pink.

I wondered if the candies were the same under the wrapping – if they were a clear peppermint or some other non-noxious flavour.

If his gaze is looking direct or to the side *none* of the candies/sweets are in his vision range. Or possibly all of them depending on how far.

I wonder if he touched the wrappers to smell and/or touch them? That to me would be a more reliable indicator of intent/desire or preference.

I remember when I was a small girl and a robot in a computer book was checking the package and compared it to the human checking the package – the feelings and the anticipation involved. [probably when I was about 14 and into the computer books in the school library – especially the programming ones].

A few years later I read Ernest the Remarkable Robot.

I also wondered if Charlie was part of the Uncanny Valley.

That showed me lots of human-computer interaction as state-of-the-art in the early and middle 1980s.

[this is probably very different from Simon Baron-Cohen though contemporaneous with his early work]

2. Autistic tendencies/features; quite a few DSMs ago.

3. Acquired brain injury when I was 3.

4. What I think about theory of mind:

I call it Teary of Mind because it can make me cry and it can be torn up at a moment’s notice and because I cannot quite put my tongue between/under my teeth.

Hmm, interesting theory-of-theory.

It has been known to get my dander up and be defensive.

I find some studies like this amusing. And I have been known to skewer them.

Feet and eyes – not much more than chance. Again, one foot will go where it is going to go.

And after a while of looking Charlie’s eyes will spin around. [Your pictures, LunaRose, don’t generally do this].

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s interesting how such a simple picture can inspire so much thought and interpretation. Simon Baron-Cohen’s experiment doesn’t do that justice.

Do we know each other from wikiHow, or are you a different Adelaide?

LikeLike

LunaRose,

I have fed back various Wikihow articles, yes. And I have appreciated your drawings in other places.

No, I have not written for WikiHow, or even read it in any great depth.

You may “know” me from The Aspergian or from Phil Gluyas’s Autism Wikia – the latter of which he gave back to the community for us to improve and look at.

Simon Baron-Cohen talks about theory of mind at three levels

* Mechanical

* Behavioural

* Intentional/inferential/implicature

based upon Leslie which in turn is based upon Grice and linguistic maxims of relevance.

The information up in the last three paragraphs is freely precissed from one of his 1989 studies which I first learnt about in January 1998.

A lot of the previous five years had been spent investigating that – the general concept.

At that point Baron-Cohen seemed more of an honest broker and less of the populist he has become today.

He wrote in 2000 a paper called “Is AS/HFA necessarily a disability?” which I read on Larry Arnold’s site. Arnold is the man who introduced me to neurodiversity through his posts on alt.support.autism and bit.listserv.autism. He is an activist and advocate from Coventry, England – and he was on the councillors board of the National Autistic Society from 2001 to roughly 2008-09.

I do like sites like WikiHow and HowStuffWorks because they help me ask and answer questions. I am also on Quora though I have not answered many questions there lately.

Currently I am feeding back about a young lady who wants to go to a convention with her friends and the friends’ parents.

We do well from minimal information – that is Noam Chomsky the linguist.

Thank you again for being open to the sciences and their interpretations and those of your readers and fellow writers, Luna Rose.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s also an Adelaide at wikiHow who’s very thoughtful. I thought you might be her, but I think she’s a lot younger than you. (I’m not sure that she existed in the late 1990s.)

Does that mean Phil Gluyas left Autism Wiki?

I hope that someday autism will no longer be a disability, and that society can fully accommodate autistic differences.

And thank you for sharing your thoughts. You seem very knowledgeable, and talking to you teaches me new things. I love learning. I appreciate you sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a very strange experiment that he ran. I’m neurotypical, but I had no clue that Charlie wanted the green candy. And I had never noticed that, in non-autistics, gaze = intent. Now that you’ve pointed it out, however, I’m noticing it about myself! That’s a cool observation that you have made!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha ha, thanks! As an autistic person, I observe non-autistic behavior very carefully, both to understand these unusual (to me) people and because I love learning about how the mind works.

I read and edit wikiHow articles, some of which are about relationships. They also say that people tend to point their feet towards where they want to go or who they like (regular like or like-like). Feet direction and eye direction are totally tools you can use to semi-accurately read the minds of non-autistic people!

Multiple neurotypicals haven’t connected “he’s looking at the candy” to “he wants the candy.” I’m beginning to think it’s rather arbitrary who does or doesn’t make that assumption.

LikeLike

Ah, another careful observer!

One way you show your care is not to jump to conclusions so fast.

There’s that whole nanosecond thin slice judgement thing.

Who is the person or who are the people who talk about feet and eyes? Nowicki and other social scientists/theorists? And there’s a particular name for Nowicki’s field – kinesics?!

And wanting would have priors to looking or otherwise handling/thinking about the candy. Along with believing and desiring.

I like your approach to understanding unusual people.

It does seem arbitrary, yes.

When I want to spell a word I look at a correct[ed] version of it. Then I break it down.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t fully understand kinesics. I imagine it’s only sometimes accurate, because humans are highly variable.

The more we observe, the more we learn. But there’s nothing quite so accurate as just asking the person how they feel or what they want. (That’s how I like to clear up my confusion.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

So do I.

Always being aware that the person can dissemble and/or lie for their own reasons and/or to spare my feelings.

#themoreweknow Luna Rose!

We are highly variable and often random.

As you did it’s good to get a good pool of data and anonymise it.

What you did was not so far from the spirit of the Cochrane Collaboration.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Ha ha, yeah!

My data is very unscientific, of course, being collected from people who are all related to each other (except Mom and Dad technically). But it was fun to collect nonetheless.

LikeLike

1) I knew that Charlie was looking at the green candy. I could not figure out which candy he wanted, however.

2) I’m neurotypical, and have been neurotypical my whole life.

3) I agree with the comment above! Brains ARE weird. That’s what makes them interesting, no?

LikeLiked by 2 people

That’s interesting!

I totally agree. Brains are super cool. Scary to look at, but interesting to study.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t know if I find brains too scary to look at.

Maybe to touch [with fingers; not with tongs or standard equipment].

LikeLiked by 1 person

Frankly, any proximity to a human brain (not contained properly in a body) would freak me out.

There was one at a science museum. It was hidden inside a box, and if you chose, you could press a button that would light up the box so you could see it. I did not get close to that box.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow. Glad you didn’t get close to that box; knowing your sensitivities and proximities.

I remember first exploring neurology and brain science in a book in the junior section of our library.

My first vision of a brain would have been in the later 1990s in a jar in the science museums.

There is a wonderful exhibition called Mind if anyone is interested.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I just get creeped out by stuff!

Oh wow, the late 1990s? I was observing bugs in jars and listening my dad read The Wizard of Oz to me back then.

LikeLike

LunaRose:

I too had a few bugs in my life – especially a bug catcher – which was given me Christmas 1991.

Good for the strong-backed-bug season and bugs who lose their skins/shells.

Now I love to look at free butterflies and centipedes and all the busy insects who pollinate our farms and gardens.

Ah – yes – the Wizard of Oz! That was a big story in my life too – especially the movie Return to Oz and the Wizard of Oz.

Was very fortunate to see it as a play in September 2004.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a little girl, I would catch bugs with a net in the field, then put them into jars with holes in the top. They’d be set free soon afterwards. It was a lot of fun.

My high school actually performed The Wizard of Oz as a play once. I watched it with my dad and sister, I believe.

LikeLiked by 1 person

1) I interpreted Charlie’s intent as them wanting the green candy.

2) I’m autistic (eyy)

3) A bit alexithymic? I can kinda know what I’m feeling but it’s not very detailed (I know that I feel bad, but not what kind of bad. Hungry? Tired? Sensory stuff? Bored? Who knows! Certainly not me.)

4) Brains are weird.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes, brains are totally weird! They’re so strange and I love them.

I’m somewhat alexithymic too, and I also have difficulty figuring out physical sensations. I literally go around troubleshooting my stomachaches (Anxiety? Hungry? Need to use the bathroom?).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve often thought SBC’s experiments ridiculous. I hadn’t come across this one before but I totally agree with your conclusions.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks!

Yeah, his early work especially has shown a very flawed understanding of autism. It’s very deficit-focused, kind of like he sees us as hollow zombies or soulless computers.

I think he may have changed his views since? But IDK.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not just that. His ideas about male brains vs female brains have been proven to be nothing more than misogynistic drivel. It’s not just Autism he knows nothing about. And he’s doubled down on that so I don’t think he’s for changing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wait, he really doubled down on that ridiculous male/female brain idea? Even though brains are almost completely* a gender-neutral body part?

Wow. Yikes. He sure loves his stereotypes.

*I read they did find a spot where they think gender is located in the brain; they saw that transgender people’s brains matched their self-identified gender when they looked at that part of the brain.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yup, he was scathing about Gina Rippon’s book The Gendered Brain, where she pointed out flaws in his methodology. He got quite defensive about it.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Wow, really? I never heard of that one.

LikeLike

An interesting point about that spot in transgender brains, LunaRose!

Wondered if it was a part that turns on selectively in AFAB or AMAB, or a part which is on all the time [as far as all the time can be in a brain].

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t really know. Admittedly, my understanding of the physical working of the brain is extremely limited.

I do know it was another way they scientifically validated the existence of transgender people (which was heartening to me). I don’t think scientists fully understand that area of the brain either; it sounds like they had only just recognized its role in gender.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mine too, though I would call it in relation to myself “very limited”.

And that cusp of recognition is really powerful. You clear the way like an ice hockey pitch to get to your goal – which is more learning.

Very heartening.

It is something to believe and then something else to know. Or to know for so long and then finally have your beliefs in congruence with them and with the facts/reality.

This applies to transgender.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I’m so glad transgender people have scientific research to help tell them (and tell others) about who they are. The scientific community can stand behind them now as they seek recognition and access to therapies. The haters can’t hide behind “science” as an excuse anymore! Trans people are real, and there’s no logical reason not to be kind to them.

LikeLike